Memory & learning

Lesson objectives

- Remember the quantitative limit of human memory

- Distinguish between desirable and undesirable cognitive load

- Evaluate cognitive load associated with a learning task

- Create a formative assessment that maximizes germane cognitive load

- Describe strategies for teaching students with very different skill levels

Overview

In this section, we will be learning more about human memory and how our this understanding can help in effective teaching strategies. Specifically, how to remove unnecessary “load” in order to facilitate learning.

From Last Time

As a reminder, the first few weeks of this workshop series are going to be focused on the process of skills development. We consider this from the perspective of the student and identify best practices that we can use as instructors. Much of what we will talk about will have a desired outcome of building capacity and confidence in data and computational skills development, rather than memorizing specific tasks.

The Limits of Memory

Learning involves memory. For our purposes, human memory can be divided into two different layers. The first is called long-term. It is where we store persistent information like our friends’ names and our home address. It is essentially unbounded (barring injury or disease, we will die before it fills up) but it is slow to access.

Our second layer of memory is called short-term. This is the type of memory you use to actively think about things and is often called working memory. It is much faster, but also much smaller: like about 7 +/- 2 things! This is why phone numbers are typically 7 or 8 digits long: back when phones had dials instead of keypads, that was the longest sequence of numbers most adults could remember accurately for as long as it took the dial to go around and around.

If we present our students with large amounts of information, without giving them the opportunity to practice using it (and thereby transfer it into long-term memory), they will not retain the material as well as if we present small amounts of information interspersed with practice opportunities. This is yet another reason why going slowly and using frequent formative assessment is important.

Exercise

This website implements a short test of working memory: https://miku.github.io/activememory/. Take the test and, if you are comfortable, share your answer in the collaborative document.

Strategies for memory management

Because short-term memory is limited, we can support students by not flooding their short term memory with too many separate pieces of information. Does this mean we should teach fewer concepts? Yes! However, this is not the only approach to use. We can also assist by providing strategies and exercises to help them form the connections that will (a) support them in holding more things in short-term memory at once and (b) begin to consolidate some concepts, moving them into long-term memory.

Formative assessment is a key component in helping students solidify their understanding and begin transferring ideas into long-term memory. Why? Because it engages the brain in retrieving recently-learned information and actively applying it to solve a problem. This helps to both reinforce and connect that new information in useful ways.

The limitations of short-term memory are one reason why assessments should be frequent: short-term memory is limited not only in space, but also in time. If you wait too long before deploying a formative assessment, some of the information necessary to complete the task will already be forgotten. This time window can be very short, especially if a lot of content is being taught at once. Be sure to remind students about prior concepts essential to a task.

Elaboration, or explaining your work, supports transfer to long-term memory. This is one reason why teaching is one of the most effective ways to learn! Group work can feel uncomfortable at first and consumes time in class, but students often rate group work as a high point for both enjoyment and learning.

Reflection is another tool that can help students review things they have learned, strengthen connections between them, and consolidate long-term memories. Like formative assessment, asking students for feedback can double as both a source of information and an effective consolidating prompt, as providing feedback demands some reflection on what has been learned. We will talk more about methods for this in the next section. You may also wish to pause and allow students to write summary notes for themselves or otherwise ask them to review what they have learned at various points in the class session.

In the same vein as “going slowly,” it is important to limit the number of concepts introduced in a class. This can be hard! As you are reviewing a lesson to teach, you will doubtless come across related concepts that are very useful, and you may feel strongly motivated to sneak them in. Planning your lesson with a concept map can help you not only identify key concepts and relationships, but also to notice when you are trying to teach too many things at once.

Exercise

Consider the strategies for memory management we just covered (formative assessments, group work, reflection opportunities, and limiting concepts) and either:

- Provide an example of how you have used one of these strategies in your teaching experience; or

- Describe how you might adopt one of these strategies to implement in your future teaching practice

Add your answer to the collaborative document.

Exercise

Discuss in your group how you have used (or want to use) formative assessment in the classroom. Specifically, address:

- How can you use formative assessment in a large (lecture-style) class?

- What other types of formative assessment have you used (we discussed multiple choice questions previously)?

- What challenges have you faced / do you anticipate in using formative assessments?

Attention is a limited resource: Cognitive Load

Memory is not the only cognitive resource that is limited. Attention is constrained as well, which can limit the information that enters short term memory in the first place as well as interfere with attempts at consolidation. While many people believe that they can “multi-task,” the reality is that attention can only focus on one thing at a time. Adding items that demand attention adds more things to alternate between attending to, which can reduce efficiency and performance on all of them.

The Theory of Cognitive Load

There are different theories of cognitive load, but for our purposes, we will consider three things that students have in their heads while learning.

- Things they have to think about in order to perform a task (“intrinsic”)

- Mental effort required to connect the task to new and old information (“germane”)

- Distractions and other mental effort not directly related to performing or learning from the task (“extraneous”)

Cognitive load is not always a bad thing! There is plenty of evidence that some difficulty is desirable and can increase learning. However, there are limits. Managing all forms of cognitive load, with particular attention to extraneous load, can help prevent cognitive overload from impeding learning altogether.

One way to manage cognitive load as tasks become more complex is by using guided practice: creating a structure that narrowly guides focus on specific skills and knowledge in a stepped fashion, with feedback at each step before transferring attention to a new feature.

Attention management

The choices you make as an instructor may add to or subtract from your students’ cognitive load. Supporting memory consolidation can reduce load later on in the class, as it reduces the effort of recalling forgotten material. You can also minimize cognitive load by choosing formative assessments that are narrowly focused and by considering potential distractions in what you display during instruction.

There are many different types of exercises that can focus attention narrowly and help to avoid cognitive overload. Carefully targeted multiple choice questions can play this role. A few more that you may wish to consider are:

- Faded examples: worked examples with targeted details “faded” out - essentially fill-in-the-blank programming blocks. e.g. students would fill in the blank a for loop in R:

# Print square of i

for (i in 1:10) {

i_squared <- _______

cat(i, "^2 = ", i_squared)

}- Parson’s Problems: out-of-order code selection & sorting challenges. e.g. students would rearrange the steps into the correct order for a differential gene expression workflow:

- Sequence samples

- Count number of reads per gene

- Map sequences to genome

- Identify differentially expressed genes

- Trim adapters from sequences

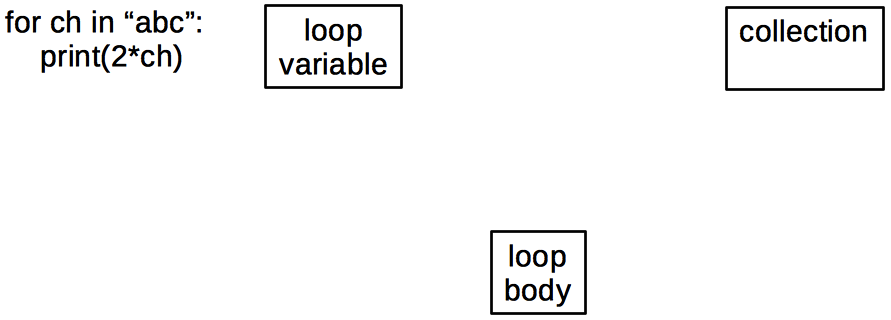

- Labeling diagrams or flow charts. For example, you could provide the concepts for the for loop in Python example and ask the students to draw lines between concepts and label the relationships.

Beware assessments that are too open-ended, as these are very likely to induce cognitive overload in novices. You may have experienced some overload already when you were asked to create a concept map; this is why we do not recommend these as an activity for novices. Questions that ask students to both remember and synthesize or reason with new information are also risky. If you try out a question and get a room filled with silence, you may need an icebreaker, you may need to re-teach… or you may only need a more narrowly focused question.

Exercise

Consider a topic you teach or might teach in one of your classes and create an assessment like the ones we described above (multiple choice questions, faded examples, Parson’s problems, or diagram labeling). You can build off of the concept map you built previously, or choose a different topic. After creating this assessment, explain how you expect it to reinforce what you taught.

Managing a diverse classroom

You will most often have students from a variety of backgrounds and with varied technical skill levels in the same classroom. Some may be novices in one technology, but competent or even expert in another. As an instructor, you will need to be attentive to this range in your students’ prior skill level. This idea of “meeting students where they are” can be tough, but there are strategies to employ to ensure a positive learning experience for all.

Exercise

What are some of the challenges you might expect when teaching students with a broad range of expertise? How have you handled situations with different skill levels in your classroom? Are there situations you have yet to “solve”? Add your thoughts in the collaborative document.

Here are some strategies to deal with this issue:

- Be sure that course advertisements communicate its level clearly by describing not only the topics, but also the specific skills and tasks (you can communicate this through your learning objectives, which we will talk about shortly).

- During class, encourage students to help others when they feel comfortable doing so. Teaching is a great way to level up learning. Note that you may need an icebreaker before most students will take this advice.

- Do not let advanced students take over the conversation during class, no matter how interesting it may be. This can alienate beginners and consumes precious time. Advanced questions and comments can be politely reserved for office hours.

- If you have help in the class (teaching assistants, preceptors), these folks should be vigilant for students who are falling behind and intervene early so that they do not become frustrated and give up. Frequent reminders to your students to indicate their progress will support your team in targeting problems in time. We’ll talk more about how to assess progress in a bit.

No class can possibly meet all individual training needs. However, it is entirely possible for total beginners and advanced students to come away happy from the same class. Beginners may not yet feel competent, but they may build a mental model of the domain and develop confidence that they can learn these skills because they have successfully walked through them. Advanced students may enjoy picking up “tips and tricks” or having their own self-taught approaches validated.

Dealing effectively with different skill levels does take some planning. However, with appropriate advertising and team cohesion on priorities and strategies, your workshop can be a worthwhile experience for everyone.

Homework

In the upcoming sessions, we will be focused on the classroom. We would like you to start thinking about topics you have taught or would like to teach that involve hands-on components to them. We will be using those topics to guide the next set of exercises.

Feedback on the day

Your instructor will ask for you to provide feedback on this session.