Motivation & demotivation

Lesson objectives

- Identify authentic tasks and explain why teaching them is important

- Demonstrate strategies for avoiding dismissive language

- Develop strategies to avoid demotivating students

Overview

Teaching and learning are not the same process. Considering what we talked about before regarding the limits of memory, we can make choices that facilitate the cognitive processes necessary for learning to occur. But any technique can fall flat when our students are not motivated. Worse, demotivation is contagious! Teaching or sharing a classroom with demotivated students is not fun or rewarding and it can be tempting to blame students for spoiling the classroom experience.

It is true motivation is influenced by many factors well beyond the control of an instructor, including individual background and systemic forces. However, there are many things you can do to cultivate motivation in your classroom, and perhaps most importantly, to avoid doing harm to your students’ motivation.

We are going to talk about several ways that students can be motivated (or demotivated!) by instructional content and approaches, and provides practice opportunities for you to become confident in motivating your students.

Exercise

Think back to courses you have taken and consider things that the instructor has said or done that you found motivating. Start by sharing your example in the collaborative document. After you have added it, we will discuss these experiences in breakout rooms. When we come back together as a group, we will have the opportunity to discuss themes or unresolved questions about these experiences.

Motivation

Authentic tasks

People learn best when they care about a topic and believe they can master it with a reasonable investment of time and effort. Many scientists might appreciate the value of programming but believe that developing useful skills will take more time than they have available. This presents a problem because believing that something will be too hard to learn often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

One way to combat this problem is to begin a lesson with something that is quick to learn and immediately useful. It is particularly important that students see it as useful in their daily work. This not only motivates them, it also helps build their confidence in us, so that if it takes longer to get to something they find useful in a later topic, they will persist with the lesson.

I saw a nice summary of this approach that was a riff off Michael Pollan’s three simple rules for eating that goes something like:

- Write good code

- Not too much

- Mostly plots

(the original rules were “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”)

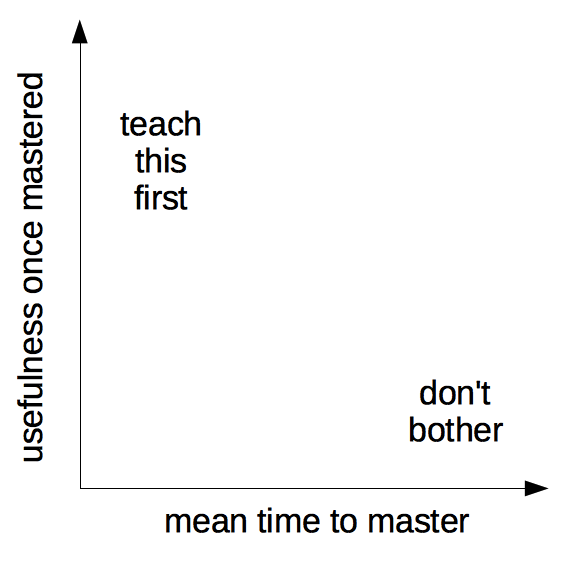

Imagine a graph whose axes are labeled “mean time to master” and “usefulness once mastered”. Tasks that are quick to master and immediately useful should ideally be taught first; things in the opposite corner that are time-consuming to learn and have little near-term application should be avoided for short data science modules.

Invite Participation

Motivation is supported by active engagement. Participation allows students to ask questions, which can resolve roadblocks quickly, and demonstrate knowledge, which helps build confidence. However, I think we have all experienced how many students will not immediately feel comfortable speaking up, especially when they feel confusion or doubt. Creating a motivating classroom means being explicit about inviting communication and reinforcing that invitation with an attentive response.

Exercise

In your breakout groups, share how you have invited participation from students. Have you tried anything that did not work as expected?

A few ways to invite participation are:

- Establish norms for interaction. This can be done by creating procedures for communication, e.g. turn taking in discussions or encouraging quieter people to contribute. Having, discussing, and enforcing a class code of conduct also provides a framework for positive communication to occur.

- Encouraging students to learn from each other. Working in pairs encourages students to talk through their learning process, reinforcing memory and making it more likely that confusion will be expressed and resolved. This can also address challenges of varying background experience: asking more advanced students to help beginners can maximize learning for both.

- Acknowledging when students are confused. Acknowledging and exploring confusion with kindness rewards students for sharing vulnerable information. Furthermore, When students see that others are confused, they are more likely to share their own uncertainties.

Demotivation

Exercise

Think back to courses you have taken or taught and consider things that the instructor (this might be you!) has said or done that was demotivating. Share your example in the collaborative document.

First, Do No Harm!

When learning a skill we develop opinions about tools and methods, and sometimes base a professional identity around displaying technical expertise. Technical boasts, insults, and other showy moves present serious hazards in the classroom! Here are a few things you should not do:

- Talk contemptuously or with scorn about any tool or practice, or the people who use them. Regardless of its shortcomings, many of your students may be using that tool, and may have invested many years in learning to do so. Convincing someone to change their practices is much harder when they think that you disdain them.

- Dive into complex or detailed technical discussion with the one or two people in the audience who clearly don’t actually need to be there. Reserve those conversations for office hours or follow-up emails.

- Pretend to know more than you do. People will actually trust you more if you are frank about the limitations of your knowledge, and will be more likely to ask questions and seek help. This is tough, because it is important that your students view you as qualified to teach the material, and we have probably all encountered precocial students (or faculty), who want to show how smart they are by tripping up the instructor. Nonetheless, be aware of where your limits are and don’t hesistate to use the “I’ll follow up on that” response.

- Use the J word (“just”) or other demotivating language. These signal to the student that the instructor thinks their problem is trivial and by extension that they therefore must be deficient if they are not able to figure it out. It is tempting to use this language in an effort to convince students that a task is as easy to learn as it is for you to accomplish. Saying something like “Look, you just clone the repo locally, checkout a new branch, make the edit, commit, push, submit a PR and boom, you’re done.” in an introduction to GitHub is likely going to have the opposite effect from what was intended.

- Take over the student’s keyboard. It is rarely a good idea to type anything for your students. Doing so can be demotivating for the student (as it implies you don’t think they can do it themselves or that you don’t want to wait for them). It also wastes a valuable opportunity for your student to develop muscle memory and other skills that are essential for independent work.

- Express surprise at unawareness. Saying things like “I can’t believe you don’t know X” or “You’ve never heard of Y?” signals to the student that they do not have some required pre-knowledge of the material you are teaching, that they don’t belong in the class, and it may prevent them from asking questions in the future. (For more on this see the Recurse Center’s Social Rules).

It can be difficult to avoid these demotivators entirely. Some people are so used to complaining about certain tools that they initially fail to realize they’re doing it while teaching. If you catch yourself doing this, you might find a way to walk it back, or consider how you might repair or improve your motivational efforts on your next interaction. Teaching yourself to avoid these types of comments takes practice, but is well worth the effort.

Reflection

Exercise

Considering the actions we discussed to make classes a positive learning environment, what is one thing you could start, stop, or change in your teaching practice to create a more positive learning environment. If there is something you want to change, but do not know how, add that to the collaborative document. If possible, discuss this as a group.

Homework

In the next session, we will work on laying the foundation for a data science module you could teach in your class. Please be prepared to provide a brief description of the tool, resource, or skill you want to teach your students. This is just a start! You will not be expected to have much other than a general idea of what you want to teach. We will have time in the next session to focus more on the how and the details of what.

Feedback on the day

Your instructor will ask for you to provide feedback on this session.